by Barbara Berry Bailey

In celebration of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, Gather is carrying out a series of conversations with 21st century women who offer perspectives on the role of churchwomen. We hope to add some new images to those we instantly think of (such as Katie Luther or Argula von Grumbach) when we hear “Reformation,” giving us a sense of where our own stories as well.

APRIL ULRING LARSON

As the first Lutheran woman elected to the office of bishop in North America, and the second Lutheran woman elected bishop in the world, the Rev. April Ulring Larson served as bishop of the La Crosse Area Synod of the ELCA from 1992–2008.

What it was like to serve as our first woman bishop, especially since you were elected in a synod where you were not rostered?

April: After allowing my name to be considered, I went through a series of forums with six other candidates. The people in the La Crosse Synod felt they got to know me. Of course, you don’t get to ask THEM questions. After the election, there was a photo in The Lutheran magazine of me smiling. Then later, you ask yourself, “What happened? [Now] I have to go to a different region where I don’t know the [other] bishops … how are they going to feel about me?” I even had a list of women in my mind who I thought would have been better choices to be the first woman bishop of our church. After a few weeks, the question came to me: “Who do you think should have done this? You have a fabulous spouse. You have wonderful children. You have the unbelievable support of in-laws, siblings and parents, and the person who does this should have a great support system.” And that is when I came to myself.

It’s hard for people who have never had to do something like that because everywhere I went people wanted to hug me, hold my hand, touch me—and it’s not about me. What they needed was a symbol of hope. And you need a support system that allows you to be a symbol of hope and promise and freedom for women.

I was never in a Bible study with other clergy women until I was done with my three terms [as bishop] and returned to parish ministry. I was where God had placed me. [As] the first woman in the Conference of Bishops, I was always in heaven when [ELCA Office of the Secretary staffer] Mary Beth Nowak would come and talk to us about where our next meeting would be, [changing] the dynamic in such a dramatic way. [Laughter] The guys are wonderful, but it’s just the way we [as women] communicate. It doesn’t mean we always agree, but [as women] you nod your head to encourage the person, support the person. Without that, it can be profoundly lonely.

Was it lonely?

April: For a couple of years, and then there was [South Dakota Synod Bishop] Andrea [DeGroot Nesdahl]. And people got Andrea and April mixed up. Once [women bishops] became more “normal” for the church, it was so much easier.

WYVETTA BULLOCK

As the first African American female executive in the ELCA, the Rev. Dr. Wyvetta Bullock, assistant to the presiding bishop and executive for administration of the ELCA, lifts up some giants whose shoulders were instrumental for her journey.

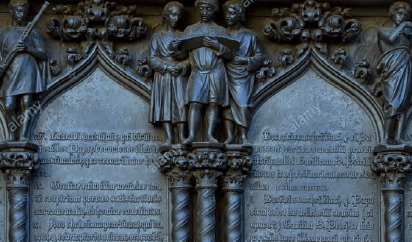

Gather: We are all “standing on the shoulders of giants,” an expression attributed to Bernard of Chartres, but familiarized by Sir Isaac Newton in 1676. Who are some of those giants for you?

Wyvetta: I came to the Lutheran church through my stewardship work with the Lutheran Church in America [an ELCA predecessor]. At that time, two African American women executives mentored me: Carolyn Green, who worked on a “Living Waters” curriculum to help people of color see themselves in the story of this church and in God’s word; and Dorothy Ricks, an associate in ministry. They were passionate and energetic about their faith and about being Black and Lutheran and what that meant. These women were not ordained.

As a long-serving churchwide leader, you have seen an unedited story of the church, so to speak. how does what was left on the cutting room floor still influence us as a church?

Wyvetta: Going to the ELCA Constituting Convention, for people of color and women there was an issue of the representation principle, later known as “quotas.” There was considerable struggle because [many] male pastors expressed that they felt they were losing their seat at the table; that people of color were taking their seats.

Women were always strong lay leaders…but it was a slow evolution for women [to become] executives in the churchwide structure, and even slower for Lutheran congregations to [extend] calls to women, although more women were graduating from seminary. For women of color it was even slower.

LILY WU

Lily Wu is a lay Lutheran and writer.

Gather: In your lifetime, what changes have you seen in the role and status of women?

Lily: I grew up in True Light Lutheran Church, the first Chinese Lutheran Church in North America, a Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod congregation in New York City. I was active in the [youth group], choir, etc., until I was in my 20s. I was noticing and questioning the role of women in the church. They were wrestling with issues such as whether a woman could be a Sunday school superintendent. During mid-week Lenten services, adult women who had grown up in the church were never approached to do a homily, [yet] 14-year-old boys would come to us and ask us what they should say.

I said to my pastor, “You know the LCA ordains women and does multicultural outreach.” He said, “Yes, I saw [your departure] coming. Go with my blessing.” I started working as a writer at the LCA and learned all sorts of new things about being a Lutheran.

Such as?

Lily: The advance of multicultural ministry, with the Rev. Drs. Albert (Pete) and Cheryl Pero, became my main filter for how I continued to engage with the church. Later when I served at Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service (then based in New York), I was still able to work with the LCMS. I was always involved with Lutheran Peace Fellowship as a board member, as well as with the women’s initiative, directing the shape of the organization, and writing and editing.

Most of all I learned God has a purpose for us, wherever we are, however we are made. I am an extreme introvert and tend to prefer to be alone in my own space. However, my work in the church drew me out and allowed me to connect with others in my own way. As a writer, I can go swimming in words. As an editor, I call myself a gem-polisher; I make others’ work shine.

This article is excerpted from the March 2017 issue of Gather magazine. To read the full story or more like it, subscribe to Gather.