Late-nineteenth century New Jersey could be a difficult place for a young woman from a poor German-immigrant household to gain a foothold. Clara Maass was the eldest daughter of a large, economically struggling family. She needed to work hard from an early age.

Despite her limited circumstances, Maass’ fortitude and courage gave her brief life enduring significance for millions. Each August 13, the church commemorates her life as a “renewer of society” (Evangelical Lutheran Worship, p. 16).

Maass was born in 1876 in East Orange, N.J. With the exception of a brief, unsuccessful stint on a country farm, her childhood years were spent in the tenements. She worked from an early age as a “mother’s helper,” a position for which she earned only room, board and the opportunity to attend school. At age 15, with three years of her high school education complete, she applied for a position at the Newark Orphan Asylum. Maass worked seven days a week to earn $10 per month, half of which she sent home to her mother.

Maass’ childhood years were a formative period for the development of hospital-based medicine, both in Newark and throughout the United States. The city’s large German American community rallied to construct the Newark German Hospital in 1870. While the hospital quickly grew in size and prominence, skilled nursing care was a persistent deficiency. The hospital’s leadership decided to begin a nurse training school. Local benefactor Christina Trefz donated a building to house nurse trainees. By 1893 the institution was dedicating the newly built Trefz Hall and ready to welcome its second class of students: women between the ages of 20 and 40 “of good character and with proof of physical ability.”

Maass was only 17 in 1893. She could easily have seen the hospital’s regulations as set in stone. Despite this obstacle, she went to see nursing school director, Anna Steeber, in person and pleaded for a place. Legend has it that when Steeber saw Maass’ work-reddened hands, she recognized a young woman who was used to hard labor. Steeber bent the rules and accepted Maass into her program. By 1895, the 19-year-old was a fully trained nurse. Just three years later, at age 21, hospital directors named Maass head nurse. Accounts of her time in Newark record that she viewed nursing as a way to care for both body and soul; she wanted to follow the example of Christ as healer.

Just as Maass took her new position at Newark German Hospital, her country went to war against Spanish colonizers on the island of Cuba. The Spanish American War would eventually be fought in both Cuba and the Philippines. Then and now it was a controversial conflict; Americans disagreed, and continue to disagree, about the justice of the war and its aims. For a young woman who’d had little opportunity for adventure, however, service in Cuba was an exhilarating way for Maass to serve her country and carry on her mission of healing. There was just one problem: the Army would not accept female nurses.

Army medical officers assumed that female nurses would only become necessary if the conflict proved exceptionally lengthy or severe. Cuba’s tropical conditions, however, proved more dangerous than the battles themselves. Soon the need for “contract” nurses was readily apparent. Surgeon General George M. Sternberg overcame his earlier reluctance to female nurses as he recognized the improvements 25 years of professional nurse-training programs had wrought. The Daughters of the American Revolution began screening applications, including Maass’ query. In August of 1898, physician and DAR vice president Anita Newcomb McGee was hired by the Army to process contract nurses under the rank of acting assistant surgeon, and Maass was on her way to Florida.

Tropical diseases felled many more American soldiers than combat. Serving in Jacksonville, Fla. and Savannah, Ga., Maass and her colleagues stayed very busy. They nursed soldiers suffering from dysentery, malaria and typhoid fever. Late in the fall Maass finally made her way to Cuba itself. Serving in Santiago de Cuba, she encountered yet another tropical malady: the dreaded yellow fever, referred to by soldiers as “yellow jack” for the Navy flag used to signal quarantine.

Maass’ Army contract ended in February 1899. Native insurgents in the Philippines, however, proved resistant to American domination of their country, producing a continuing need for soldiers—and medical care. Watching from New Jersey, Maass was impressed by Surgeon General Sternberg’s reputation both as scientist and as compassionate healer. Sternberg, a fellow Lutheran, strove to care well for sick and wounded soldiers. Maass wanted to be a part of these efforts. She wrote the Surgeon General’s office directly to ask if she might again be of assistance. On Nov. 20, 1899, Maass received two hours’ notice to board a ship bound for Manila. She again served soldiers felled by typhoid, malaria and the dreaded “yellow jack,” but this time, Maass’ strong constitution failed to protect her. The not-quite-24-year-old nurse contracted a bad case of dengue fever, often referred to as “break-bone fever” for the painful sensations it caused. She did recover, but lingering weakness led the Army to send her home to New Jersey.

During the months of Maass’ Philippines service and recovery, the United States Army in Cuba began a new effort to determine the cause of yellow fever. Army officials undertook large-scale hygiene campaigns. These massive fumigation and disinfection efforts all but eliminated some previously endemic diseases. They failed, however, to prevent a new yellow fever outbreak in 1899. Santiago alone reported over 200 cases, with a 22.8 percent death rate. Furthermore, yellow fever was not just a Cuban problem; periodic epidemics in the United States had caused more than 100,000 deaths since 1793. “Yellow jack’s” high fevers, delirium and el vomito negro, or black vomit caused by broken blood vessels in the stomach, conjured a terror unmatched by most other illnesses. The U.S. occupation in Cuba, then, posed a unique opportunity to overcome this scourge once and for all.

Army Major Walter Reed was appointed to chair a Yellow Fever Commission with the assistance of contract surgeons Aristides Agramonte, James Carroll and Jesse Lazear. Major General William Gorgas, the Chief Sanitary Officer of the City of Havana, and contract surgeon Juan Guitéras also took part. Reed was intrigued by the contention of a U.S.-trained Cuban physician, Carlos Juan Finlay, that the vector of yellow fever transmission was a mosquito: the Aedes aegypti, to be precise. Finlay had never been able to prove his hypothesis, so Reed and his colleagues set out to do so themselves. The Yellow Fever Commission labored under controlled circumstances to produce yellow fever using either mosquitoes that had bitten infected individuals, or the effluvia of infected patients—testing, once again, a hygienic approach toward eliminating yellow fever. Subjects were paid $100 to participate, and another $100 if they contracted the disease. The effluvia were disgusting, but safe. None of the volunteers exposed to this waste contracted yellow fever. Subjects exposed to mosquitoes during certain incubation periods, however, became ill. Sadly, Dr. Lazear contracted yellow fever from his own experimentation and died.

Meanwhile, Maass had recovered from her bout of dengue fever and continued to feel the pull of service in Cuba. The Yellow Fever Commission, convinced they’d isolated yellow fever’s culprit, dispersed in February 1901. Drs. Gorgas and Guitéras, however, continued work on both mosquito eradication and efforts to produce immunity via mild cases of the illness, a tactic fairly similar to early inoculation for smallpox. Maass greatly admired Gorgas for his reputation among the troops she had served in Santiago. Once again, she worked up the courage to offer her assistance, writing to ask if the doctor could use her help in his Las Animas Hospital. Gorgas consented. Once in Cuba, Maass entreated Gorgas and Guiteras to let her participate in their experiments. Focused, as ever, on her Christian mission as a healer, she believed immunity would help her to more effectively nurse her patients. Maass’ tenacity overcame the doctors’ hesitation. She became the only woman—and the only American—to participate in this round of experiments. Maas was bitten numerous times in March, May and June of 1901 with only minimal results. A bite on Aug. 14, 1901, however, produced a much stronger effect. By Aug. 18, Maass was gravely ill, and Gorgas began a series of increasingly alarmed telegrams to her family in New Jersey. Despite the best care available for yellow fever, Maass died on August 24. Her faith sustained her to the end: Maass’ last letter to her mother began, “Goodbye, Mother. Don’t worry. God will care for me in the yellow fever hospital the same as if I were at home.”

Maass’ most immediate legacy was to bring an end to human experimentation in yellow fever research. Long-term, however, her bravery and desire to serve became a model for others. In 1923, Leopoldine Guinther became superintendent at what was now known as Newark Memorial Hospital. She became curious about the portrait of a young woman that hung in the nurses’ sitting room. Initially, the most she learned was that Maass was “a former chief nurse.” Four years later, however, Guinther happened upon an item in the “25 years ago today” column of the Newark Evening News that brought Maass’ heroics back to public attention. “The body of Clara L. Maass, who died of yellow fever in Cuba, has been shipped to Newark and there buried with military honors,” she read. Inspired, Guinther began a campaign to gather information about Maass that took her as far as Cuba. She raised funds to place a monument at Maass’ grave that explains her life and work. The engraved plaque ends with the words, “Greater love hath no man than this.”

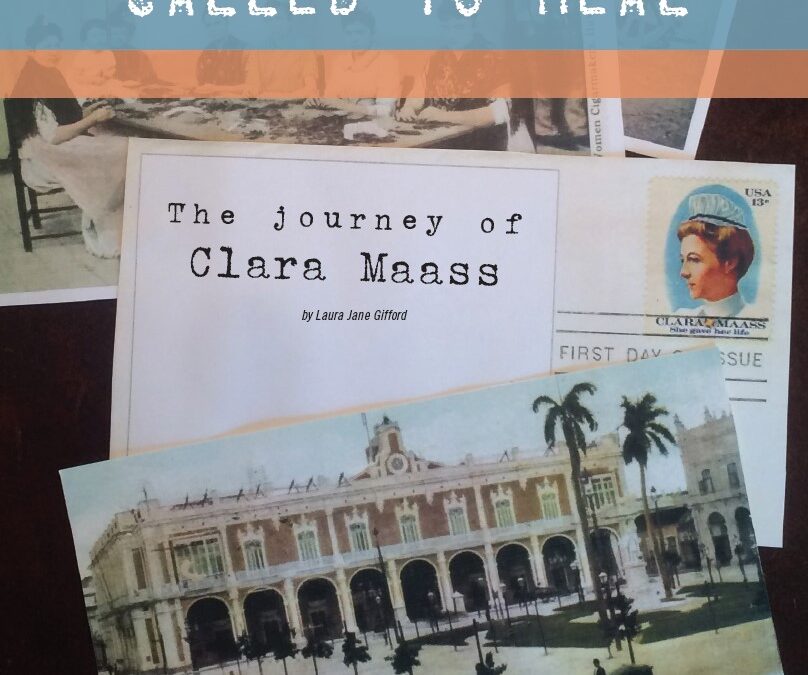

Awareness of Maass ebbed again following Guinther’s departure from Newark Memorial, but by the 1940s the hospital—now called Lutheran Memorial—and its most prominent heroine gained a new patron in Lutheran pastor Arthur Herbert. Among other things, Herbert was an enthusiastic philatelist. At his urging, Maass was featured on several hospital Christmas seal stamps, and Herbert’s efforts to secure a U.S. Postal Service stamp featuring Maass paid off on the centenary of her birth in 1976.

Maass’ most significant honor, however, is one she would have found unimaginable as a 17-year-old nursing student in 1893. On June 19, 1952, Lutheran Memorial Hospital was renamed the Clara Maass Memorial Hospital. The Clara Maass Medical Center and Clara Maass School of Nursing remain an active presence in New Jersey to this day. This hardworking East Orange, N.J., girl now represents healing and hope in her community.

Laura Gifford is an ELCA deacon and holds a Ph.D. in American history. She is an acquisitions editor with Fortress Press. Laura lives in Portland, Oregon, with her husband, daughter and cats and is a member of Resurrection Lutheran Church, Portland.

This article appeared in the July/August 2016 issue of Gather. To read more like it, subscribe to Gather.

Thanks for sharing this inspiring storl